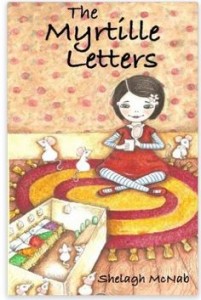

Author: Shelagh McNab

Self-published; Amazon

This is the most wonderful story – almost the book I’d like to have written myself, if I’d actually got round to doing it rather than just talking about it!

Set in France, this children’s story (with an age band of 9-12, though I feel it can be read by younger and grown-up readers) has seven-year-old Molly as its main protagonist. Her family has just moved to France and everything is a bit new and strange. She discovers her resident tooth mouse (there are no tooth fairies in France) and a magical friendship begins. The author takes us into a world most of us would never have imagined existed, but the story is gritty and realistic too. There are also some wonderful and useful snippets about life in France and in particular the French language – funny and useful in equal measure for the Francophiles among us. Some of the chapters have short explanations at their start to introduce you to French sayings which will come in useful as you read on.

McNab has captured wonderfully well the child’s perspective – the book is written in the first person so the story comes to us through the eyes of Molly.

It is not a very well known fact but in France, there are no tooth fairies. Instead when you put your tooth under your pillow a little mouse, the tooth mouse, takes your tooth away.

Originally just available on Kindle as an ebook, it’s now also available in paperback. As it’s a chapter book without pictures, the ebook is a good option unless you like to read a solid book. The link to Amazon is here.

As a technical aside, I have the ebook version and there are a few pages where the font is, inexplicably, in yellow which makes it very difficult to read. These things happen when editing and converting into ebook form. But this is easily remedied by simply highlighting that section as you read it, or you could play around with font options.

Inside the shoebox was a row of nine tiny beds, all beautifully made out of wood, each with a blanket and a tiny pillow. The pillows had been embroidered with an initial in the tiniest sewing and the bedcovers had been thrown back as if the mice had all jumped out of bed when we disturbed them.

I have not done this book justice with my review and may well write about it in more detail at a later date. I wish more people knew about this book, and I hope Shelagh McNab has some more up her sleeve, as I’d certainly love to read more.